For Mothers and Daughters.

Men.

Have you ever in your short life wondered what it must be like to be a woman in this day and age?

Love in the time of the Virus.

Again, I must apologize to Senor Marquez, Columbian maestro of magic realism, renowned for masterpieces such as Memories of My Melancholy Whores, One Hundred Years of Solitude. And of course, Love in the Time of Cholera.

His work does remind me of one other great writer, Albert Camus who produced the masterful The Plague. Africa should be so proud. Always just remember that Camus was not only French – he probably spent many a year musing through the streets of Paris, eternal city of Love – he was Algerian.

And yet still. Men. Forgive me for saying this but how can Africa be proud, the way it continues to treat its women. Call me a rabble-rouzer, I really don’t care anymore what you think of me, but I cannot stand by idly while you, a Zulu King, can pick and choose any virgin, old enough to be your grandchild, to deflower – or rape? – at any damn time you damn well please.

You call it the annual Reed Dance. I call it Mass Rape. A man does not necessarily need to rape a woman physically. He can do it with his eyes. If I must have the courage of my convictions, then I must be prepared to make that acknowledgement. Yes, I too, have wondered what it must be like to wantonly take a woman and do as I please with her.

And in the transaction, the exchange that takes place between a man and what is impassively referred to as a sex worker – she’s been called many names; prostitute, whore, harlot, Gentoo. I cannot excuse my loneliness. Or even my curiosity. I’m ashamed to say it. But there it is.

Sexual fantasy. And much, much worse.

And before you judge me.

Be very careful. How is plowing a woman with one drink after another a more acceptable transaction? It’s not a fair trade, and she’s the one who ends up paying, sometimes with her life.

Sexual fantasy. Taking what you can get when your own woman cannot or will not.

I can’t blame her.

It simply isn’t right.

Goodwill. King of the Zulus. What a name! King Shaka must be rolling in his grave. Do I hear the Ancestors calling? Go roll your bones for all I care. Yoweri Museveni, the strutting, longest serving president of Uganda. What despicable, despotic Idi Amin could not do, he appears to have done.

And is still doing, lock-down or no lock-down.

And yet.

No. It just isn’t right what Museveni and many Ugandans continue to do to so many lesbian women and gay men over there. And trans-gendered women too. Ugandans’ claim to fame is selective appropriations of the Holy Bible, otherwise known as the Word of God. Go on. Go read the Book of John. This is a predominantly Catholic country, by the way.

Bench warmers over there obviously missed Pope Francis’s famous sermon in which he proclaimed;

‘Who am I to judge?’

He could only have been inspired by Jesus Christ, our Lord and Savior, because it was He who said; let he who has cast no sin, cast the first stone. And yet. Have the victimized really sinned? Because it seems to me that they are mostly in it for the Love. And why not take what He said literally. Love your neighbor as you love yourself. It’s how you feel inside, your heart, right? Love your wife, man, if you have one. A heart. Do not hurt her. Do not abuse her. If you cannot love your wife, you cannot love yourself. Instead of beating her to a pulp, why not beat yourself up.

Until you get it right in your head.

Until that day comes, as far as I am concerned, women are off limits to you. But who am I to judge? Certainly, women are off limits to me as well if I cannot love them. I cannot love them if I cannot love myself. But today, I feel glad. After all this time, I must love myself after all. The lock-down owing to COVID-19 could not have come at a better time.

But yes, I know. It is really hard. People have been losing their jobs. People have been losing their livelihoods. And people have been losing their lives. As far as I am concerned; unnecessarily. Not through the novel Corona virus. But through the regular beatings. It has been going on for years. Indeed, it is said that women and children enjoyed a brief reprieve once my country’s version of the Lock-down came down.

Because guess what, chaps; no more alcohol, read my lips, no more alcohol. And no more barroom brawls either. Hooliganism, and worse, stamped out. Overnight. Bars, pubs, shebeens closed, lock, stock and two smoking barrels. But plenty of cigarettes and crystal meth – we call it tik here in Cape Town, a city ironically named the Mother City. Smokes and meth. If you can afford it. Actually, you can’t.

Guilty as charged. What a twelve-dollar pack of cigarettes could have bought in fresh fruit and vegetables, enough to feed a poor family of five for a few days. Yes, loving in the time of the Virus is hard. Today, let me state quite emphatically that I am NOT proud to be a South African. Men, our country holds the ‘proud’ record of having the world’s fifth highest COVID-related infections in the world.

Who lies above us in this inestimable record? I tell you what; two countries stand out. Clue. They hold the record for harboring the world’s largest nuclear weapons arsenals. So much for reducing the stockpiles, Mr Obama. Anyhow, something else stands out about these two great countries. They are ruled by misogynists, one with an iron fist, the other with a limp dick.

Yes, they don’t always have nice things to say about women. And they don’t have nice things to say about me and you either. Lesbians. Gays. Bisexuals. Trans-gendered men and women. And fun-loving queer kids too. But Messrs Trump and Putin, sorry to go breaking your hearts because boy, have you got a mountain to climb.

Because, lads, you’ve got some way to go before you can catch us. We hold some of the highest records for the most beatings, most murders and, of course, proud record this, most rapes. South African-born literary luminary, JM Coetzee, was not far off the mark when he wrote his Booker Prize-winning Disgrace .

Amongst the highest rates in the world. For murder. Beatings. Rape. But here, you see, we murder our women, we beat them too. And if we’ve got time, we’ll rape them until Kingdom comes. We even correct them. We correct lesbians. Oh, we rape boys too, most of us when behind prison bars. See if you can top that, guys!

And we rape them before, during and after Holy Mass.

Disgraceful! Indeed, it’s worse than that.

Mr Coetzee packed his bags for Perth. And he actually went! The thought has crossed my mind. But I have somewhere else to go. Not to escape the harsh realities of daily life here in South Africa. Because, Julius Malema, I too am a son of the soil. And my reasons for going elsewhere are motivated by love.

Not violence. Not hate. I certainly do not hate my fellow man, but I wish he would just stop already. More has to be done to stop this scourge. And to think, just the other day I had this to say to a lady with a lamp. I said this to her. Heck! If I can survive in this country, I can survive anywhere in the world. Oh! That’s just so easy for me to say.

Because get this; I am not a woman. And while I may still tremble at times, I am still able to defend myself. But not a woman. She could try but, nine times out of ten, no. Now try and do this if you can. I tried this in the past. I have been trying in recent days. But be warned. It’s not easy to imagine yourself in a woman’s body. No, it’s not that I have gender-bending feelings from time to time, not that.

No, because in South Africa, if you are powerless as a woman, life is extremely hard. Today marks the early days of what we South Africans commemorate as Women’s Month. We wish to stand up for the rights of all women in this country, and for that matter, the rest of the world. I for one wish to stand up for the children too, those without food, and those who are beaten, and raped by their uncles.

Uncles, my arse!

I wish to stand up in church one day once the lock-down restrictions are a thing of the past and shout and scream at the top of my lungs. Stop raping the boys! That’s going to be quite a challenge for me because I’m not accustomed to raising my voice. But when it does happen, very rarely, thank God, I’m extremely angry.

Nevertheless, it’s on my mind all the time. I wonder sometimes, lovely man that he is, if it’s on Pope Francis’s mind too.

And he’s still not my father.

There’s this old English saying. Women are the fairer sex. That they are, and God Bless them for that, I adore them for that. But weaker sex? I think not. Men. Come on now. Admit it. It is we who are the weaker sex. If we’re not violent, we don’t always seem to know what the hell we’re doing. Let’s use this as an example.

Let’s look at those countries with the worst COVID-related infections in the world. And compare them with some who have slayed the virus like Wonder Woman would a demon from out there in the universe. Cyril Ramaphosa is South Africa’s State President. He’s also a billionaire. How he got his hands on that lucre is a story for another day.

Donald Trump is the USA’s President. They call him the Commander in Chief over there. Huh? Anyway, he’s a billionaire a few times over. How did he make it? Actually, he didn’t. He inherited it from his immigrant father. I’m led to believe that he still had a silver spoon in his mouth when Trump Snr handed over the poisoned chalice. And then there is that man.

Vladimir Putin.

Tsar of Russia.

Rumor had it that he was the wealthiest man in the world at one point. Prizes for guessing how he might have got to that point? And is it any wonder that our country’s former statesman, Jacob Zuma is a huge admirer? And he’s a huge admirer of women too. On the charge of raping one, here, in a court of law he was adjudged to be not guilty. For crying out loud, the man took a shower!

But today that woman is dead.

Putin the richest man in the world? Today; perhaps not. That disputable record belongs to none other than Jeff Bezos, the Amazon king. While thousands of people are losing their jobs every day as a result of COVID-19 (somehow I doubt that that’s the real reason) Jeff Bezos is making more of those billions.

Where others fall, go steal from them.

How stuff works. Go read an Amazon book.

Speaking of the Amazon. If you thought COVID-19 was bad, you ain’t seen nothing yet. Because just you wait and see what happens when Jair Bolsonaro finally burns the Amazon jungles to the ground. Putin, Trump, you can pack away your nukes, we might not need them after all. Bolsonaro, we’ll he’s a billionaire too.

And he’s a misogynist as well. Let’s not even talk about what he thinks of the beautiful Brazilian trans-gendered women over there.

But enough of these men.

Let’s talk about the women. Not for nothing is Germany’s longest serving Chancellor, Angela Merkel, referred to over there as Mutter. And today, COVID-19 is under control in Germany. It’s under control in Finland as well. But Finland’s Prime Minister is far too young to be referred to as that country’s mother.

Or is she? I ask you. Jacinda Arderne is what you could refer to as the consummate multi-tasker. Women are good at that sort of thing. Multi-tasking. And leading. You’re surprised? I’m not. Now, this gorgeous lady, first known holder of office to parade with others on Pride Day, breastfeeds her baby while running her country. And running it very well indeed. And beating the living hell out of the virus.

Just like New Zealand’s mighty All Blacks beating the crap out of our beloved Springboks. Today, the people of New Zealand are walking their streets at night without any fear. There’s no virus, you see. But it’s more than that. Because New Zealand also enjoys amongst the lowest crime rates in the world. And by that read that women and children are relatively safe.

I wish I could say the same for my country. Heck! We may be Rugby World Champions, but we’ve got nothing to be proud of over here. I’ll say it again. Jacinda Arderne. You really have outdone yourself! You’re a swell gal if you don’t mind me saying so. And it would not surprise me at all if Time Magazine makes you its Person of the Year in this year of the Virus.

Men. Forgive my emotions. Forgive my anger. I’m guilty. Don’t you feel it too?

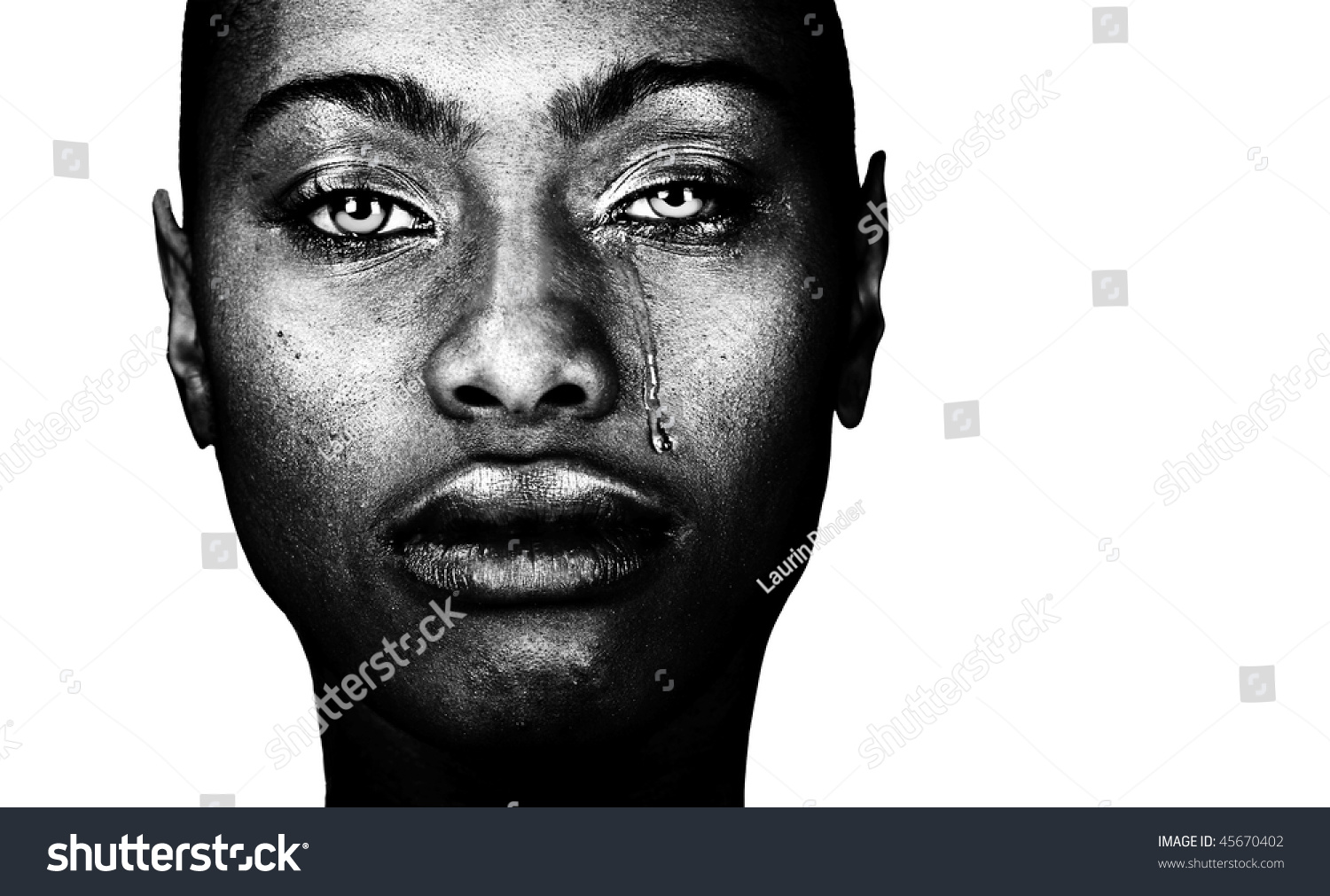

Women. I really do have tears in my eyes, no really, I do. It’s Women’s Month here in South Africa and in that spirit, I would really like to wish you well for tomorrow, come what may. I pray that it will be safe.

May God be with you.